Web working principles

Every time you open your browsers, type some URLs and press enter, you will see beautiful web pages appear on your screen. But do you know what is happening behind these simple actions?

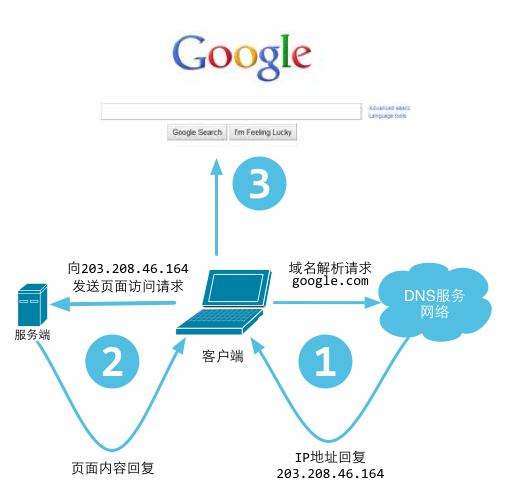

Normally, your browser is a client. After you type a URL, it takes the host part of the URL and sends it to a DNS server in order to get the IP address of the host. Then it connects to the IP address and asks to setup a TCP connection. The browser sends HTTP requests through the connection. The server handles them and replies with HTTP responses containing the content that make up the web page. Finally, the browser renders the body of the web page and disconnects from the server.

Figure 3.1 Processes of users visit a website

A web server, also known as an HTTP server, uses the HTTP protocol to communicate with clients. All web browsers can be considered clients.

We can divide the web's working principles into the following steps:

- Client uses TCP/IP protocol to connect to server.

- Client sends HTTP request packages to server.

- Server returns HTTP response packages to client. If the requested resources include dynamic scripts, server calls script engine first.

- Client disconnects from server, starts rendering HTML.

This is a simple work flow of HTTP affairs -notice that the server closes its connections after it sends data to the clients, then waits for the next request.

URL and DNS resolution

We always use URLs to access web pages, but do you know how URLs work?

The full name of a URL is Uniform Resource Locator. It's for describing resources on the internet and its basic form is as follows.

scheme://host[:port#]/path/.../[?query-string][#anchor]

scheme assign underlying protocol (such as HTTP, HTTPS, FTP)

host IP or domain name of HTTP server

port# default port is 80, and it can be omitted in this case. If you want to use other ports, you must specify which port. For example, http://www.cnblogs.com:8080/

path resources path

query-string data are sent to server

anchor anchor

DNS is an abbreviation of Domain Name System. It's the naming system for computer network services, and it converts domain names to actual IP addresses, just like a translator.

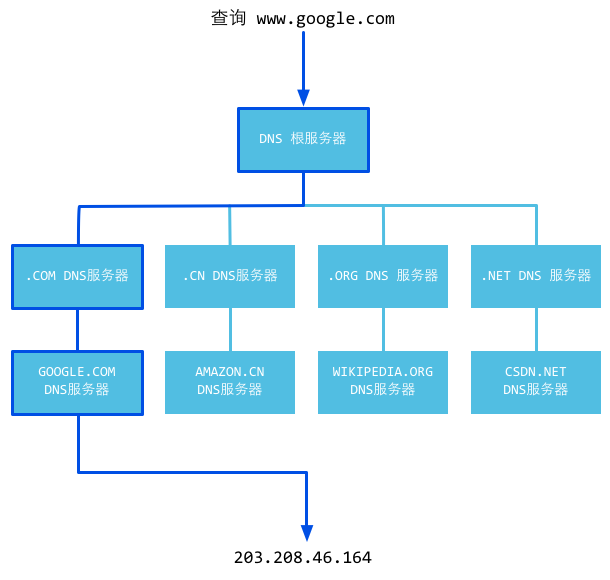

Figure 3.2 DNS working principles

To understand more about its working principle, let's see the detailed DNS resolution process as follows.

- After typing the domain name

www.qq.comin the browser, the operating system will check if there are any mapping relationships in the hosts' files for this domain name. If so, then the domain name resolution is complete. - If no mapping relationships exist in the hosts' files, the operating system will check if any cache exists in the DNS. If so, then the domain name resolution is complete.

- If no mapping relationships exist in both the host and DNS cache, the operating system finds the first DNS resolution server in your TCP/IP settings, which is likely your local DNS server. When the local DNS server receives the query, if the domain name that you want to query is contained within the local configuration of its regional resources, it returns the results to the client. This DNS resolution is authoritative.

- If the local DNS server doesn't contain the domain name but a mapping relationship exists in the cache, the local DNS server gives back this result to the client. This DNS resolution is not authoritative.

- If the local DNS server cannot resolve this domain name either by configuration of regional resources or cache, it will proceed to the next step, which depends on the local DNS server's settings.

-If the local DNS server doesn't enable forwarding, it routes the request to the root DNS server, then returns the IP address of a top level DNS server which may know the domain name,

.comin this case. If the first top level DNS server doesn't recognize the domain name, it again reroutes the request to the next top level DNS server until it reaches one that recognizes the domain name. Then the top level DNS server asks this next level DNS server for the IP address corresponding towww.qq.com. -If the local DNS server has forwarding enabled, it sends the request to an upper level DNS server. If the upper level DNS server also doesn't recognize the domain name, then the request keeps getting rerouted to higher levels until it finally reaches a DNS server which recognizes the domain name.

Whether or not the local DNS server enables forwarding, the IP address of the domain name always returns to the local DNS server, and the local DNS server sends it back to the client.

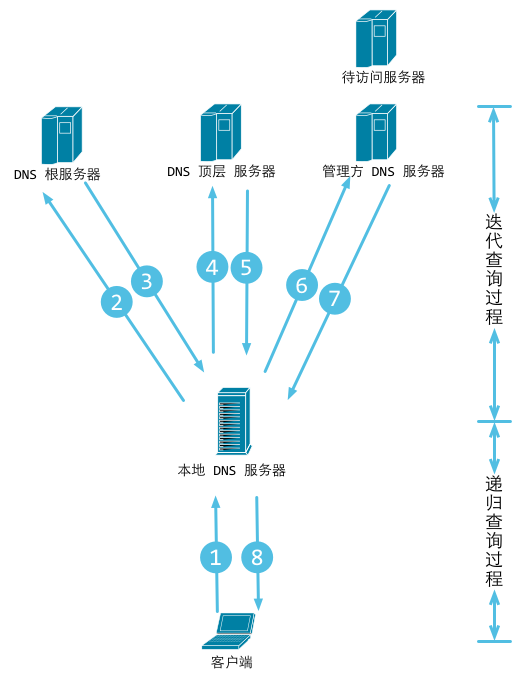

Figure 3.3 DNS resolution work flow

Recursive query process simply means that the enquirers change in the process. Enquirers do not change in Iterative query processes.

Now we know clients get IP addresses in the end, so the browsers are communicating with servers through IP addresses.

HTTP protocol

The HTTP protocol is a core part of web services. It's important to know what the HTTP protocol is before you understand how the web works.

HTTP is the protocol that is used to facilitate communication between browsers and web servers. It is based on the TCP protocol and usually uses port 80 on the side of the web server. It is a protocol that utilizes the request-response model -clients send requests and servers respond. According to the HTTP protocol, clients always setup new connections and send HTTP requests to servers. Servers are not able to connect to clients proactively, or establish callback connections. The connection between a client and a server can be closed by either side. For example, you can cancel your download request and HTTP connection and your browser will disconnect from the server before you finish downloading.

The HTTP protocol is stateless, which means the server has no idea about the relationship between the two connections even though they are both from same client. To solve this problem, web applications use cookies to maintain the state of connections.

Because the HTTP protocol is based on the TCP protocol, all TCP attacks will affect HTTP communications in your server. Examples of such attacks are SYN flooding, DoS and DDoS attacks.

HTTP request package (browser information)

Request packages all have three parts: request line, request header, and body. There is one blank line between header and body.

GET /domains/example/ HTTP/1.1 // request line: request method, URL, protocol and its version

Host:www.iana.org // domain name

User-Agent:Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1) AppleWebKit/537.4 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/22.0.1229.94 Safari/537.4 // browser information

Accept:text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8 // mime that clients can accept

Accept-Encoding:gzip,deflate,sdch // stream compression

Accept-Charset:UTF-8,*;q=0.5 // character set in client side

// blank line

// body, request resource arguments (for example, arguments in POST)

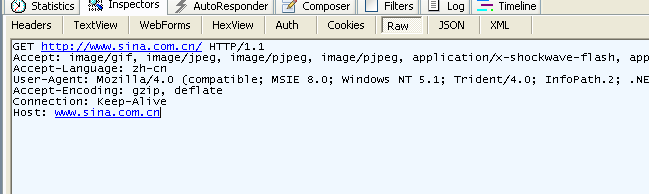

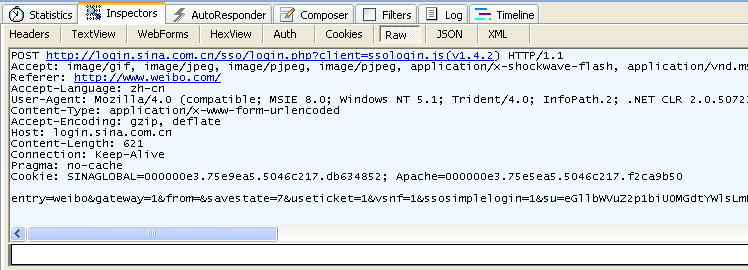

We use fiddler to get the following request information.

Figure 3.4 Information of a GET request caught by fiddler

Figure 3.5 Information of a POST request caught by fiddler

We can see that GET does not have a request body, unlike POST, which does.

There are many methods you can use to communicate with servers in HTTP; GET, POST, PUT and DELETE are the 4 basic methods that we typically use. A URL represents a resource on a network, so these 4 methods define the query, change, add and delete operations that can act on these resources. GET and POST are very commonly used in HTTP. GET can append query parameters to the URL, using ? to separate the URL and parameters and & between the arguments, like EditPosts.aspx?name=test1&id=123456. POST puts data in the request body because the URL implements a length limitation via the browser. Thus, POST can submit much more data than GET. Also, when we submit user names and passwords, we don't want this kind of information to appear in the URL, so we use POST to keep them invisible.

HTTP response package (server information)

Let's see what information is contained in the response packages.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK // status line

Server: nginx/1.0.8 // web server software and its version in the server machine

Date:Date: Tue, 30 Oct 2012 04:14:25 GMT // responded time

Content-Type: text/html // responded data type

Transfer-Encoding: chunked // it means data were sent in fragments

Connection: keep-alive // keep connection

Content-Length: 90 // length of body

// blank line

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN"... // message body

The first line is called the status line. It supplies the HTTP version, status code and status message.

The status code informs the client of the status of the HTTP server's response. In HTTP/1.1, 5 kinds of status codes were defined:

- 1xx Informational

- 2xx Success

- 3xx Redirection

- 4xx Client Error

- 5xx Server Error

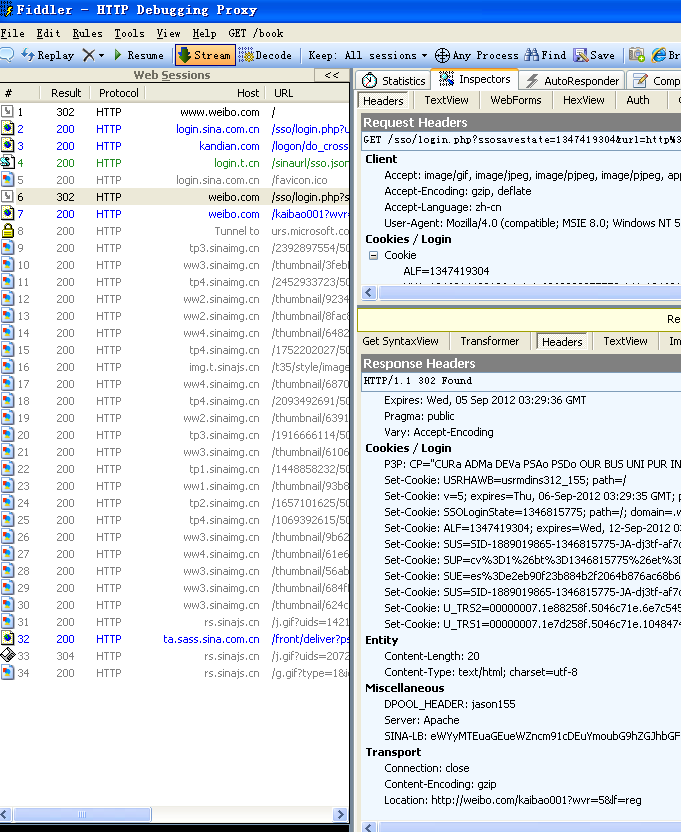

Let's see more examples about response packages. 200 means server responded correctly, 302 means redirection.

Figure 3.6 Full information for visiting a website

HTTP is stateless and Connection: keep-alive

The term stateless doesn't mean that the server has no ability to keep a connection. It simply means that the server doesn't recognize any relationships between any two requests.

In HTTP/1.1, Keep-alive is used by default. If clients have additional requests, they will use the same connection for them.

Notice that Keep-alive cannot maintian one connection forever; the application running in the server determines the limit with which to keep the connection alive for, and in most cases you can configure this limit.

Request instance

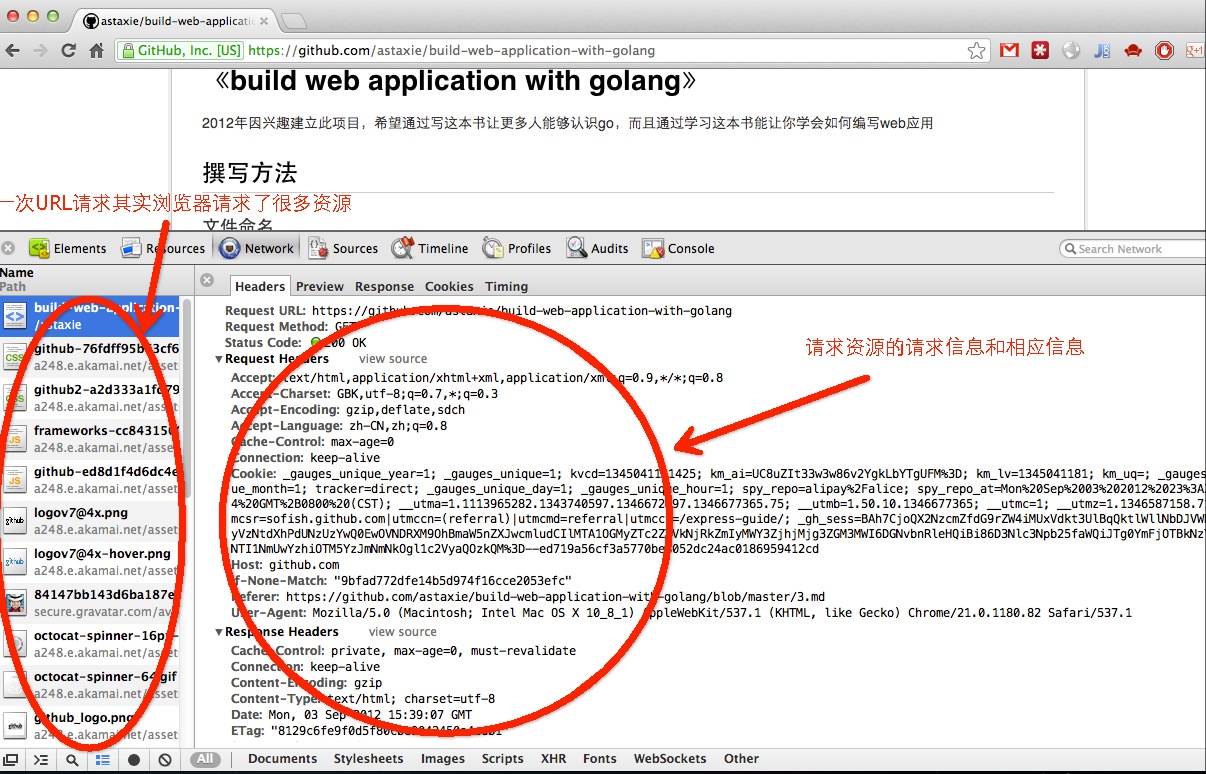

Figure 3.7 All packages for opening one web page

We can see the entire communication process between client and server from the above picture. You may notice that there are many resource files in the list; these are called static files, and Go has specialized processing methods for these files.

This is the most important function of browsers: to request for a URL and retrieve data from web servers, then render the HTML. If it finds some files in the DOM such as CSS or JS files, browsers will request these resources from the server again until all the resources finish rendering on your screen.

Reducing HTTP request times is one way of improving the loading speed of web pages. By reducing the number of CSS and JS files that need to be loaded, both request latencies and pressure on your web servers can be reduced at the same time.

Links

- Directory

- Previous section: Web foundation

- Next section: Build a simple web server